Hey so it’s Saturday, and Saturday is the day I go visit my friend Cuba in his house in the park. You may remember Cuba as the dude whose house I was at when the police showed up for unrelated reasons. I’ve been paying weekly visits to Cuba for about five months now, and today is the day I tell you how that all started.

So as I may have told you before, I went to art school. I went for a Master’s degree in writing, which meant two things:

1) Upon graduation, no one would be allowed to correct my grammar EVER AGAIN

2) Before graduation, I had to submit a thesis.

But, this being art school, my thesis could be whatever the hell I wanted. It could be a paper airplane, or a pile of dead leaves, or – in my case – a pair of gloves that allowed the wearer to type by pressing the fingers to the palms in combination, similar to chording a guitar. As part of my project, I attached the gloves and a webcam to a beat up old laptop, wrote a program to superimpose any text I typed over the webcam video, and went walking around my neighborhood. After twelve hours of this, I ended up with about an hour of useful footage and a pile of molten slag where the laptop used to be. Luckily, it wasn’t my laptop.

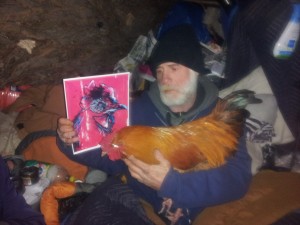

This is what I looked like.

Most of the usable footage wasn’t any good , but I did find something interesting in the course of my journey. When I sat down to rest on a bench in the park, I looked out across the pond and saw what appeared to be a little grey shack.

It was built on a tiny peninsula that stuck out into the pond, and it would have been hidden by a weeping willow if the trees had had any leaves. As I came closer, filming all the time, I saw that the shack was made of what appeared to be grey carpet samples, tied together at the edges with the plastic twine sometimes used to tie up newspapers. I stood in front of the shack, typing to myself, when I heard a sudden movement inside.

“Oh shit,” I typed, and ran. I didn’t know who was inside the shack, but I figured they wouldn’t respond well to a twitchy cyborg hovering outside their door. Then I chased a goose for a while, and more or less forgot about the shack.

But every time I walked through that park (and I walked through it a lot, to get to the restaurant where I worked) I would find myself peering over my shoulder at the mysterious shack. Month after month, it stayed standing. Occasionally I would see a dumpy white woman in a red sweatshirt standing outside, smoking. One day she came into my restaurant to use the bathroom. I didn’t think to ask her about her shack until she was already gone.

I worked at that restaurant all summer, and the whole time I worked there I never had the courage to approach the shack. As the weather warmed up, I started seeing more and more people gathered around the place. I assumed the woman in red was the primary occupant, but maybe I was wrong. Finally, on the day I put in notice at the restaurant (because fuck restaurants) I mustered up the gumption to go say hi.

There was a muddy path worn into the grass where it passed through the willow tree. I emerged, still in my all-black server clothes, in front of two people squatting on milk crates. One was the woman in red, her eyes cloudy and her jaw drooping malevolently. The other was a straight-backed man with a bushy white beard, a grey t-shirt and a castro cap.

“Who the fuck are you?” said the woman.

“I’m … I’m [Publius Ovidius Naso], and I just see you guys over here all the time and I wanted to know what was going on.”

“Why the fuck is it any of your business?” she spat.

“I’m sorry,” I said, “I’ll go away if you want me to. I was just curious.”

“Come here asking all these questions,” she said, “You’re a cop, huh?”

“Nope,” I said, “Not a cop.”

“Ey, papi!” said the man with the beard. “Come on, sit down.”

“Are you crazy, Cuba?” said the woman, “He could be a cop!”

“Ee not a cop, papi, come on. Sit down right here, papi. You no listen to her. This my house.” He patted a broken milk crate next to him, and I sat.

“Fuckin’ stupid,” said the woman, “He could be a cop and you let him sit right here.”

“Shaddap!” yelled Cuba, waving her away like a cloud of flies, “Shaddap! Ee not a cop! This my house!”

The woman left us alone, grumbling the whole time, and Cuba turned to me.

“Dey call me Cuba,” he said, “Because I from Cuba. Whatchoo name, papi?”

And then we were friends. I sat on that milk crate for two hours, listening to the story of Cuba’s life. He’d come from his home country on an inflatable raft twenty years before, and worked his way from Florida to Chicago, where a forklift accident damaged his spinal cord and paralyzed him. After submitting to an experimental surgery that left a scar on his back the whole length of his spine, he could walk again, but he couldn’t work. He’d never been much of a drinker before, but now he drank a 40 a day to keep the pain at bay.

As for heroin, the drug of choice in that park, he’d never touched it. That, and the fact that he was the only person with a house in the park, made him a sort of father figure to all the junkies in the area, black and white alike. His little clearing was and is probably the least segregated area of Chicago. The junkies brought him change to buy cigarillos and 40s, and he kept a few ampules of Narcan in a repurposed baby-wipe box in his hut, in case any of them overdosed. My first day there, I watched one of them hide in his house to shoot up. Cuba waited until the guy was done, then kicked him in the leg until he sat up and gave Cuba back his headlamp.

The animals in the park saw Cuba the same way as the junkies did. The rats and squirrels showed up daily for scraps, choosing to converge when most of the other humans were gone. Cuba had raised two of the squirrels himself after their mother was killed by a hawk the previous winter. And there was the rooster.

Garfield – named for the park where he lived – was the king of the camp. Everybody who came by brought him an offering. He pecked at everything he was given, until a little before sunset when he retired to the branches above Cuba’s shack. Cuba had found him abandoned in the park when he was just a baby (there are a lot of wannabe urban farmers in the neighborhood) and the two had been fast friends ever since. From my perch on the milk crate, I watched Cuba lovingly stroke Garfield’s comb. I couldn’t believe any of this shit.

By the time I left, he had decided that I was his honorary son. He had a few of those, but I was the only one who wasn’t on dope. He told me to come back any time, and to tell anybody who gave me trouble that Cuba was my father.

When I came back the next week, I didn’t see Cuba anywhere. But there was a skinny black guy with white powder smeared across his face, and eyes rolled back in his head. He smiled when he saw me, and shook my hand.

“Hey man!” he said, “Good to see you! Where’s that ten bucks you owe me?”

“I don’t owe any money,” I said, “I’m here to see Cuba.”

“Nah man, you remember. We went in on a bag together. You still owe me ten bucks.”

“No,” I said, “I really don’t.”

“You a good swimmer?” He asked me, smiling.

“I’m alright,” I said.

Without warning, he grabbed me by the shoulders and made to toss me in the pond. But as soon as he laid hands on me, Cuba was on him, tackling him into the pond. He spent the next ten minutes chasing the poor guy from bank to bank, waving a kitchen knife. No one ever fucked with me after that.

I could go on and on about Cuba, and the relationship we’ve developed over the last few months. But let me just say this: I’ve always believed that the money I give any beggar on the street is worth it if I’m repayed with a story. But I learned from Cuba that the relationship doesn’t have to be transactional. He told me today that me and Garfield are the only friends he has here. He doesn’t have family. And I’ve spent enough time begging for rides to know how lonely you can get when everyone knows you need something from them. So I guess my point is, every once in a while when you see someone on the street, try giving them a couple words, even if you don’t have a dollar to trade for a story. A lot of homeless people are assholes, for sure, and I’ve met most of them, but there are guys like Cuba, too, begging downtown with his rooster in tow. And if you don’t start a conversation, how are you gonna know who’s who?

Well, I mean, I guess you could look for the rooster…