If you, like me, are a fan of the TV show Survivor, you may have noticed that many players self-sabotage in the mid-game. People get a few successful episodes under their belt and start thinking “Man, I ought to do something to really distinguish myself from the other contestants. What if I, for example, betray my closest ally? That’ll show everyone how unique and dynamic I am!!!” Fans of the show call this “big-move-itis”, and it’s almost always a dumb strategy. Players are valuing the uniqueness of their gameplay over the effectiveness of their strategy. It’s a bad idea in Survivor and it’s an even worse idea in creative writing.

I’ve seen it from students, from peers, and from supervisors. No one is immune. We are so inundated with content that it’s easy to feel as if we’ve got to do something tangible in order to make our stories unique. And if M. Night Shyamalan has taught us anything, it is that the most reliable way to make a story unique is with a thrilling twist. Just as the contestants on Survivor can’t wait to betray their allies in order to prove how clever they are, we writers are constantly tempted to betray our readers in order to prove that we were one step ahead of them all along.

And this works, sometimes! M. Night Shyamalan’s career gives us a very clear idea of just how infrequently it works. The dude hasn’t had a hit since Unbreakable. Having a reputation for out-of-nowhere twist endings, with nothing else of real substance to back it up, is kind of a death sentence. Once you know a guy is always trying to prank you, you stop letting him come into your house and balance buckets of paint over all your doorways. The poor guy has a classic case of big-move-itis, and it looks like it’s terminal.

What, then, is the cure? One thing that’s helped me is looking at examples of writers and entertainers who very clearly do not give a shit about surprising their audience. The first book that really made me think about this was Cat’s Cradle, by Kurt Vonnegut. In it, Vonnegut has a character give a very detailed description of a theoretically apocalyptic superweapon, Ice-nine, and then deny that it could possibly exist. If this were your average thriller, we’d spend the rest of the book wondering whether it does exist, before learning, in the climax, which character was secretly hiding it all along. But one sentence later, Vonnegut goes and says this:

There was such a thing as ice-nine. And ice-nine was on earth.

He literally does not give us even one sentence to wonder whether Ice-nine is real. And that shit is not even relevant for another twenty-five chapters! That knowledge is just free-floating, totally unnecessary, but he gives it to us anyway because he can’t be bothered to keep it a secret. In fact, twenty-five chapters later, when Ice-nine comes up again, it’s because Vonnegut is busy telling us that the new characters he just introduced are hiding it in their luggage. Again, this will not be relevant for quite a few pages, and the story’s narrator doesn’t even know about it yet! I thought about putting spoiler tags on this paragraph but then I realized that Vonnegut literally could not care less.

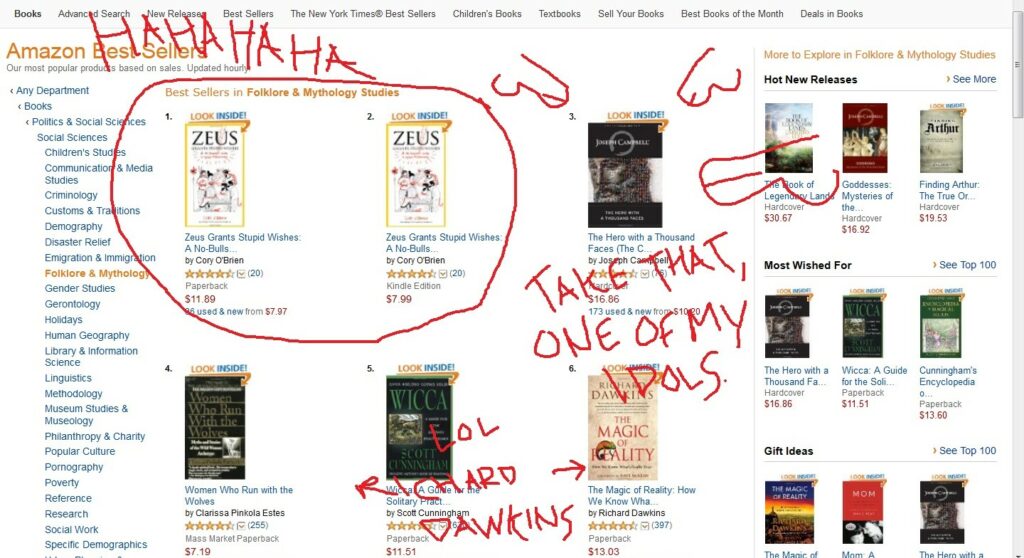

Sometimes — I’d argue usually — readers are more intrigued by things they know are coming than things they don’t. We know this. We know about Chekhov’s Gun. We know about Dramatic Irony. We know that Oedipus Rex is a banger even though the ending has been spoiled for literal millennia. I myself built my early career on retelling stories that everyone has already told. And yet when I am constructing a plot I still find myself fighting the overpowering urge to take the least obvious turn at every juncture. It comes from a lack of confidence in my work; the fear that if someone is allowed to look at my writing head-on, they’ll notice all its flaws. But that’s what makes openness such a baller move.

The greatest magic trick I’ve ever seen was performed by Daniel Madison on an early episode of Penn and Teller’s Fool Us. Go ahead and watch the video. I’ll be over here summarizing it. Here’s what happens:

- Daniel Madison tells everyone he’s going to deal a royal flush from a shuffled deck of cards, blindfolded

- Daniel Madison deals a royal flush from a shuffled deck of cards, blindfolded.

There is no confusion about what he is going to do. There’s no real suspense about whether or not he’ll actually do it. And yet, because of the sheer impossibility of the premise, it’s fascinating to watch. At the end of the trick, after some deliberation, Penn tells Daniel,

“I think we might be more impressed because we know what you did.”

He did not fool them! That’s literally the whole premise of the show, and he did not do it. He did something better. He amazed them, by putting his cards on the table with undeniable skill. That is what we should aspire to as storytellers — not tricking our readers, but performing tricks, tricks which are no less impressive when you know how they’re done.

Survivor players who succumb to big-move-itis don’t usually win. They tend to burn out before the late game, victims of the unnecessarily complicated game states which their own moves have created. The players who do win are the ones who carefully choose their moments, and make big moves in the service of some greater goal. Good twists exist, and there are plenty of reasons to hide information from your readers. But if you don’t know why you’re doing it, it’s probably best to let your case of big-move-itis run its course.