Since Joseph Campbell first described the Hero’s Journey in his “Hero With a Thousand Faces”, it has seized the popular imagination. Lots of people have based their whole careers on it: Dan Harmon, whose “circle theory” of story crafting has netted him a lot of creative success; George Lucas, who literally rewrote Star Wars after he read Hero with a Thousand Faces; Stanley Kubrik was into Campbell too, and so are the dozens if not hundreds of screenwriters and bloggers peddling books that promise systems guaranteed to help you write your way out of creative block. So clearly the Hero’s Journey works. Harmon and Lucas and Kubrik are all very successful, and some of their stuff is pretty good! And man, I would love to believe that there is a universal human story which transcends time and culture, which speaks to something deep in our collective unconscious. That would be so convenient. Because if there was really only one story, or at least only one good story, that would mean everybody could just write that and we could solve fiction forever! But…

The monomyth is not, in fact, the only myth. It turns out there are other stories, too. And what’s crazy about it is that those other stories are often the same stories that we impose the Hero’s Journey onto. Check it out: some linguists did a study where they showed the same video to speakers of a bunch of different languages. This is the video they showed them. It’s a pretty normal video. Some stuff happens in it, then it’s over. What’s interesting is what happened when the researchers asked speakers of different languages to describe what they’d just seen. It turns out people had wildly different answers depending on their native tongue. Think about how you would summarize that video. If you’re like most English speakers, you probably tried to come up with a rough narrative chronology of the things that happened. But you could just as easily have ignored the events altogether and described the landscape, the way speakers of some other languages did. Events that some speakers skipped were vitally important to others. What people described had very little to do with what was actually there, and much more to do with who they were.

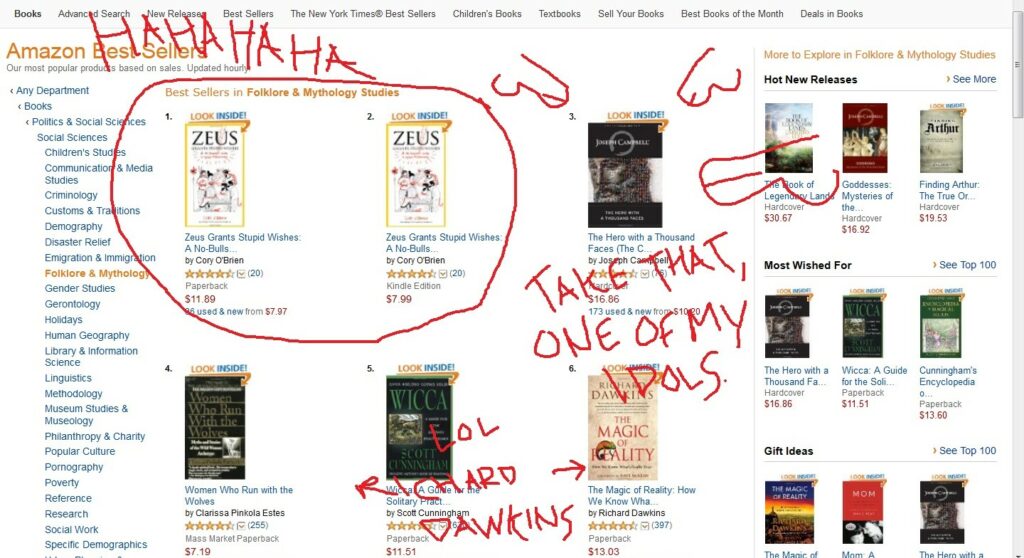

Joseph Campbell published The Hero With a Thousand Faces in 1949. At the time, psychoanalysis was a new field, and everybody was just getting acquainted with the works of Freud and Jung. Campbell’s concept of the monomyth is heavily influenced by Jung – just as a lot of modern thinking about stories still is today! But we’ve had more than seventy years of philosophy since Campbell. It’s time to admit that he didn’t discover something that was secretly true about all stories the whole time. Joseph Campbell, a white, American dude from the 1940s, came up with one possible reading that happens to fit a lot of stories, and a significant number of our most influential writers and filmmakers since then have been following his formula like it’s scripture and not, you know, an interpretation of scripture. I think it’s high time that someone (me) stood up and challenged Campbell’s beloved interpretation – and not just because my book briefly outsold his on Amazon.

Just like with the video in the linguistics experiment, there are other ways to describe the same stories. And if we truly want to advance as a culture, I think it is the responsibility of our storytellers to explore new ways of seeing and telling stories. Because there is one part of the Hero’s Journey that is badly in need of revision: The Hero.

No, I’m not saying we need fewer heroes and more gritty antiheroes. I’m not even saying we need fewer heroes and more “regular dudes.” No, I’m straight up saying we need fewer heroes period (and also fewer dudes, but that’s another essay). To me, the central problem with Campbell’s monomyth is that it focuses on the transformation of a single person.

Think about A New Hope. Think about Iron Man. Think about A Clockwork Orange. All of them center around the trials and transformation of a single individual. Now think about Jeff Bezos. Elon Musk. Donald Fucking Trump. Think about every rich asshole who’s collected an army of simps by selling the bogus idea that they made it entirely on their own. It might seem kind of bonkers to draw a straight line between A New Hope and Donald Trump (though less crazy to connect Iron Man and Elon Musk). But it’s not so much about who these stories center. It’s about what these stories exclude: communities.

We live in an era where the individual is all but powerless in the face of environmental collapse, corporate plunder, and rampant political corruption. But you know who’s not powerless? All of us, together. As long as we think of ourselves as individuals, as the “heroes” of our own separate “journeys,” we will remain isolated from each other and incapable of collective action.

The stories we tell each other, and how we talk about those stories, has a profound effect on our thinking. To that end, I believe it’s time we turn our attention away from the monomyth, and towards better myths – myths that acknowledge our collective power rather than deluding us about our individual strength. But where can we find examples of this new type of collectivist storytelling? Well, let’s go back to Star Wars…

Now, I don’t much care for Star Wars. I was too young to develop an emotional attachment to the original trilogy, but exactly the right age to be disappointed by the prequels. To their credit, most Star Wars fans I know have made no effort to “convert” me (something I sadly cannot say for most Star Trek fans I know), so when a number of my friends suggested that I watch Andor, knowing full well that I don’t give a fuck about space wizards, I gave them the benefit of the doubt.

And yeah, Andor slaps. But the interesting part, at least to me, is why it slaps. The main-line Star Wars trilogies are each about a very special boy (or girl) who is so good at the force that the whole galaxy is like “whooooaaaaaaaa.” Andor, on the other hand, is about a guy who accidentally shoots somebody on the way home from the club. Except it’s not even actually about that guy. Yes, his name is the title, but there are some episodes where he basically isn’t on screen at all. That’s because Andor is not about a person. It’s about groups of people.

It’s about the fascist apparatus of the Empire which grinds into action when some pompous bureaucrat insists on filing Andor’s accidental murder through the proper channels. It’s about the coalition of rebels who take advantage of Andor’s fugitive status to enlist him in a sweet heist. It’s about the citizens of his home planet, under military occupation. Individuals within those groups have opportunities for heroism: making a speech that incites an oppressed populace to riot, for example. But none of these people are heroes all the time, and none of them are elevated above the groups they’re a part of. They’re regular people who, because of their connections to the people around them, have a fleeting opportunity to do something incredible, before that opportunity moves on to someone else.

It’s inspiring to watch. Empowering even. Unlike the Hero’s Journey, which makes me think “ah, man, wouldn’t it be nice if I were that cool and powerful?” stories like Andor make me think, “Oh man, I guess you don’t actually have to be that powerful to change shit.” It feels achievable. It points to where our strength truly lies.

These kinds of stories are all over the place, we just don’t think to categorize them that way because we’re too Campbell-pilled to notice. Dungeons and Dragons – and all of the actual play series that have contributed to its recent rise in popularity – is a hugely collaborative form of storytelling, where there can’t be a single hero because that wouldn’t be fair to all of the other humans at the table who also want to be heroes. These stories by their very nature focus on the developing relationships between the characters, rather than one character’s developing relationship with themselves.

But for my money, the genre which best exemplifies this structure is the noble heist film. Ocean’s Eleven, Money Heist, Leverage, and so many others focus not on the journey of a single individual, but on a group of like-minded people coming together to accomplish a shared goal. Yes, most heists include a mastermind who gets a bit more screen time, but the heists themselves, which take up the bulk of the film, are intensely collaborative and provide moments for each character’s unique skills to shine. The loot is often split evenly among the participants, or given to a member of the community in need. And when it’s not, it’s usually because someone tried to fuck over the rest of the group to get a bigger share. Either way, heists are about trust, accountability, and eating the rich. Fuck Joseph Campbell, this is the energy I’m bringing into 2024.

And guess what, knuckleheads? That show Andor I was talking about? It’s got a fucking heist in it. And you know what else? The Dungeons and Dragons movie is also a heist movie. If you put a community of like-minded people together, sooner or later they’re going to hatch an elaborate plan to steal a bunch of shit from a rich guy who deserves it. So yeah, maybe that’s why wealthy screenwriters are so intent on keeping Campbell on top, huh?